For the past two weeks, I’ve taken a break from my field playback experiments. One reason for the scheduled break is to work on wedding planning and begin some data analysis from my first three weeks.

The data collection didn’t stop, and for my lab-mate Jeff Clerc, it was just beginning. Jeff just finished his first year of graduate school with my advisor, after receiving his bachelor’s degree in wildlife at Humboldt State. I volunteered to help Jeff train assistants for bat capture, and to help with bat handling, since the assistants are just finishing their rabies inoculations. We spent three days at Humboldt Redwoods and three day in Lassen National Forest catching bats, trying to specifically target silver haired bats.

For his thesis, he is interested in the population dynamics and migratory patterns of bat, specifically tree roosting bats such as silver haired bats. While found almost year round on the north coast of California, silver haired bats are generally migratory, roosting in warm inland locations during the summer and the more mild, coastal habitats in the winter. Despite our fairly intensive efforts capturing bats this past fall and winter, we rarely encounter both sex, instead catching mostly males. This leads to the question, where are the females?

Additionally, while it is generally accepted that these species migrate south and to the coasts each fall, the exact geographic locations where these bats spend summers or winters is uncertain. Researchers studying migratory birds have had strong success using feather isotope analysis to study movement patterns. Different environments have different levels of chemical isotopes, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, which can be tracked through the food web and various organisms. By analyzing the ratios of certain isotopes in a feather, scientists can determine where that particular feather was grown. There has been limited success using isotope analysis on bats using fur. While promising, this type of research on bats has two major downfalls: the exact molting and growth patterns of bats are not as well understood or regular as bird molts and even if they did, the isotopes to do provide fine scale analysis of habitat or location, but more broad geographic regions.

As aerial insectivores, bats are food limited. During the summer, they forage extensively, putting on fat stores to get them through long migrations or periods of hibernation. This extensive foraging during a relatively short period of time means that the fat composition stored during this time should bear the chemical signatures of the ingested food. Bats foraging in different locations will be feeding on slightly different insect communities, which should be reflected in their energy stores. By analyzing these fat stores, researchers should be able to determine what geographic regions these bats migrated through. The use of this fatty acid signature analysis (FASA) has been successful in some pelagic bird and marine mammals. Jeff’s thesis will test if these differences can be detected using fat removed from a bat, and if different regions result in different chemical compositions, using silver haired bats as a model.

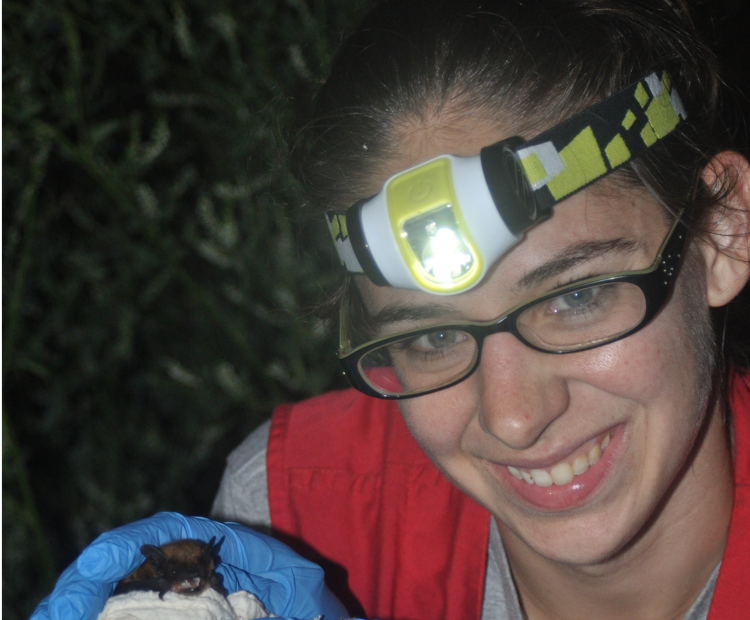

We started out netting at Humboldt Redwoods, an area we are familiar with. Surprisingly, it turns out that the coastal redwoods of California may be the only place in the world where we catch more bats in the fall and early winter than we do in the summer. Luckily, we still managed to catch a few of the target species, to collect their fat. The procedure is done with institutional and state approval, and causes minimal distress to the bats, not even drawing blood.

Batting on Lassen National Forest land was a very different story. We weren’t really sure what to expect when we headed out to the park, about 5 hours east and up from Humboldt county. It was much warmer and drier than Humboldt, and our mist netting stream spots were few and far between. This was promising, since more limited water sources meant that it would be much harder for bats to avoid our nets. It turned out bats were really not good at avoiding the nets, as we caught about 30 bats in under an hour. Under more normal circumstances, this wouldn’t be as crazy, but since only Jeff and I were vaccinated and experienced enough to take bats out of nets, it was a very busy hour. By the end of the first night we had caught close to twenty silver haired bats (male and females, as well as a few juveniles and lactating females), and several Myotis (including a new species for me, Myotis evotis (long legged myotis). Our second night we were a little more prepared, but still caught about 20 bats before shutting down the nets.

After showers at the ranger station and a trip into Susanville for more ice, we moved west about 30 miles to a slightly different field site (still in Lassen National Forest). The area was much lusher and greener than the first two nights, and we staked nets out at a pond/meadow area. After a thundering lightning storm narrowly passed by us, the temperature dropped and the insects seemed to clear out of the area. While there were still a few bats flying around, we shut down the nets after catching a few small Myotis. Then we made the long drive back to Humboldt, where Jeff will process his fat samples before heading back to Humboldt Redwoods this week.